I Am the Instrument: Pierre Bensusan Transcends the Acoustic Guitar

The French-Algerian guitarist, composer, and singer reflects on his life in DADGAD tuning, followed by a transcription of his arrangement of “Hekimoğlu”

One day early this month, Pierre Bensusan emailed me out of the blue, offering a pair of tickets to a concert he would soon be performing in Redwood City, California. I was touched by his gesture and excited to bring one of my musically inclined, junior-high-school-aged children to the show. But when we arrived at the venue, the door staff denied our entrance—I had somehow missed the conspicuous “No Persons Under 21 Allowed” sign on the door and hadn’t even considered that it might not be an all-ages show.

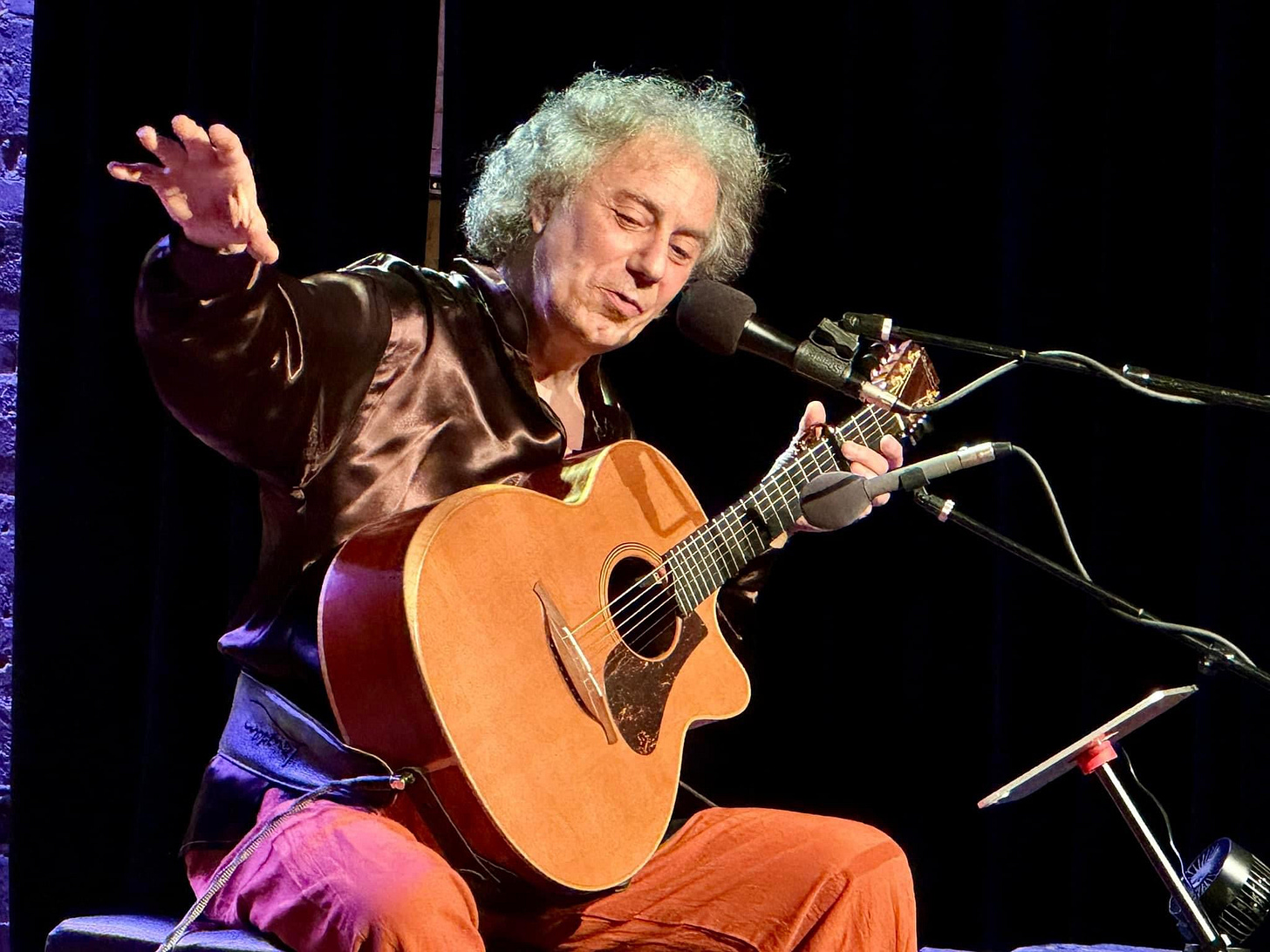

But not all was lost: with Bensusan’s kind permission, the door was left ajar so that my child and I could watch the show from the sidewalk. I was dubious that we would be able to hear much of anything, but from the first few notes of “Hekimoğlu”(transcribed at the end of this interview), the traditional Turkish ballad that is a fixture of the guitarist’s live show, I was struck by how clearly we received his music. Despite the competing sounds of one passerby blasting an evangelical radio program without headphones and another pushing a food cart with the loudest ringing bell, it was easy to hear the clarity and detail of Bensusan’s subtlest strands of counterpoint and complex chord voicings. We enjoyed a beautiful evening of music even though the circumstances were hardly ideal.

Bensusan, 66, is one of the most beloved musicians in the fingerstyle world, a master of DADGAD tuning with an orchestral command of the guitar, who synthesizes music from around the globe in an exuberant and highly personal style. The Algerian-born French musician has been making albums since he was 18, beginning with 1975’s Près de Paris, and has shared his unique philosophy of music and understanding of the fretboard with generations of guitarists through works like The Guitar Book and scores of instructional videos and transcription books.

I caught up with Bensusan on the telephone, and we chatted about his long history of touring in the United States and what it has meant to his music, his discovery of and affinity for DADGAD tuning, how music serves as a balm in these troubled times, and his long relationship with his Lowden guitars. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

You played your first string of concerts in the United States 45 years ago in the Northeast. What are your memories of your debut in this country?

My first show was in Boston. I played in the University [of Massachusetts Boston], for a class in the morning, and that same night, I played at Club Passim in Harvard Square. So those were my first ever appearances in the U.S. on the same day, in the spring of 1979. A little bit later, I opened for David Grisman at The Bottom Line in New York. I was a big fan of that record he did with Peter Rowan and Bill Keith [et al.] called Muleskinner, and so when I was offered to open for him, I was really thrilled and honored.

My remembrance of that first tour 45 years ago is very volatile, because it was such a long time ago. I was just 21, with my own car that I bought in Boston, a Dodge Dart that I got thanks to my friend Bill Keith, who found it for me. It was it was an interesting time. Jimmy Carter was president. We could not drive over 55 miles an hour because of the shortage of gas. But I had a fantastic experience, being a very young man, for the first time in a country like the United States, exploring all over the place. And three months later, I sold the car back for the same price I bought it.

On that tour, I played 33 shows being managed by Manny Greenhill—the man who created Folklore Productions and who also managed musicians like Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Doc Watson, Taj Mahal, and Reverend Gary Davis. He opened the door of the country for me. I didn’t really realize how fantastic it was at the time, being so young, but I do now that the years have passed.

What’s it been like playing here regularly in the decades since?

It’s been my most important place to play, even more than Europe. I think the reason is that there’s a lot of interest for acoustic music—and especially for the acoustic guitar—in this country. From early on, I had a great infrastructure in place. I had a manager and an agent. I had a record label; at the time it was Rounder Records. I had a PR person, an accountant, and an assistant. That team made it completely doable to come back every year, and I had developed a circuit that over the years has been strengthened.

The most difficult thing at first was for me to get a working visa. And Manny Greenhill was the one to make it happen. He fought really hard for me to get working—when I first applied for a visa, I was refused because they thought I would be taking the work of American musicians. And so Manny sent my first record to musicians like Joan Baez and Pete Seeger and asked them to share their impressions. They wrote fantastic reviews, and Manny went on appeal and won. So it’s thanks to them that I’m here, really.

You’ve played exclusively in DADGAD for the entirety of your long career. At what point did it become your standard tuning, and how long did it take you to be able to compose and improvise freely in it?

I remember finding DADGAD as I was fooling around with different tunings. One day DADGAD came to my fingers, I think in 1972 or ’73. In ’78 I made a decision to play in only one tuning and stop fooling around with different tunings. I was getting quite frustrated with going from one to the next, never getting a good intonation, breaking strings, and never really knowing my fretboard. I had to choose between the different tunings I was using, including standard and drop D, and DADGAD became obvious.

For a majority of guitar players, the preferred tuning is standard, but that tuning did not inspire me. DADGAD was the tuning that made me love the instrument so much. If I hadn’t found it, I’m not sure I would have cultivated a certain relationship with the instrument, and probably would have gone back to the piano. DADGAD really made me want to dive in and deepen the instrument itself.

I’m still working my way through DADGAD—it’s going to take a lifetime. You can never really know your fretboard inside and out because the possibilities are endless. I’m following my imagination, and my desire to compose music, and I’m finding even more possibilities to alter the flow of things in this tuning. The thing is, you have to make your ideas work in the tuning you have. When I started to study the tuning, I assumed that anything could be played in the tuning—it was just quite a different fretboard. How many fretboards can you master? For me, only one, and I’m still trying to master the DADGAD fretboard. I’m on my way.

I would say you’ve gotten quite far, to say the least… Your music is a highly personal synthesis of sounds from around the world. How have you integrated everything—through careful study or more by osmosis?

By being curious about culture, by looking at languages like musics, by being totally welcome to the idea of a borderless world: a world with empathy and tolerance, where people can go wherever they want, in function of their desires and their immediacy and their mission. For me, music is a reflection of all of us on this planet. And I think more and more that this planet is in fact very small. People have always been migrating, changing sceneries and adapting themselves to different countries, myself included. I was born in North Africa, but after the independence of the country, in 1962, when I was four, my family migrated to France, and I grew up in Paris. We lost everything we owned in Algeria, and my parents had to rebuild a life from scratch. So I have a lot of sympathy for people who want to migrate today, and this is a debate that I have with myself and in intimate settings with my family and friends.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Eclectic Guitar to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.