Long Study: Miles Okazaki on Thelonious Monk, New Music, and the Practice of Attention

A conversation about inhabiting the jazz great’s songbook, shaping new music, and the art of teaching focus—plus a transcription of “Children’s Song.”

Thelonious Monk’s music holds a singular place in the jazz tradition: concise yet inexhaustible, stripped down yet endlessly surprising. On the page the pieces look disarmingly simple, but their odd proportions and clusters have tested generations of musicians. To play them convincingly takes more than fluency in chord changes; it demands patience, restraint, and a willingness to let the music dictate its own terms. Many improvisers, even brilliant ones, have preferred to skate over the surface.

Miles Okazaki has taken that challenge as a central pursuit. In 2018 he released Work, a six-volume solo recording of all 70 Monk compositions, among them children’s songs and blues heads seldom heard in performance. Last year he returned to the project on stage, presenting 66 pieces—his own carefully considered tally—over two nights at the Jazz Gallery in New York, played entirely from memory. It wasn’t a stunt. It was a way of hearing the whole book at once, as a single landscape.

Now 50, Okazaki grew up in Washington State and has spent most of his career in Brooklyn. He studied at Harvard, the Manhattan School of Music, and Juilliard, and has been a steady presence on the New York scene since the early 2000s. Alongside his work on Monk, he has built a catalog of his own: Mirror, Generations, Figurations, the Trickster cycle, Thisness, and most recently Miniature America. These records reveal a guitarist interested not only in touch and tone but in structure and process—music that often grows from systems, patterns, or narrative shapes.

He has also been a valued collaborator, working with Steve Coleman, Dan Weiss, and many others who share his interest in complex, long-form approaches. At Princeton, where he now teaches, he works with students from a wide range of disciplines and emphasizes the value of sustained attention in a culture that encourages distraction.

In the conversation that follows, Okazaki speaks about returning to Monk, the instruments that anchor his sound, the methods behind Miniature America, and what it means to teach focus at a time when it is increasingly hard to find.

Last year you performed the complete Thelonious Monk songbook at the Jazz Gallery—66 tunes across two marathon nights. What drew you to take on that challenge, and what did you take away from it?

I’ve studied Monk’s music my whole life, and every five years or so I circle back for a deep dive. At a certain point I thought, why not try to play everything? Not just cherry-pick the famous tunes, but really get the whole body of work under my fingers. Different people arrive at different numbers—some count past 70—but I landed on 66 pieces that I feel stand on their own.

Doing them in two nights was less about showing off stamina than about exploring what it means to hold a body of work in your head and hands. It was as much about memory as about physical playing. You have to shape the set so there’s contrast—you can’t play three ballads in a row. Structuring it forced me to think of the entire book as one continuous form. And the biggest takeaway was how much Monk blurs the line between composition and improvisation. His solos were never just blowing over changes; they always circled back to the tune. That’s the lesson: use the melody as the source.

What is it about Monk’s music that keeps pulling you back?

Monk is a model of how a body of work can function. The catalog isn’t huge, but it’s incredibly dense, and it rewards revisiting. Every time you come back, you find something new.

He also represents the deep connection between composition and improvisation. Those two things can seem separate, but to me they’re just two sides of the same coin. Composition is usually slower—you can refine details on paper that you couldn’t produce in the moment. But improvisation gives you rhythmic and structural ideas that you’d never rationally invent. Monk’s improvisations always had that structural weight, because they were tethered to the composition itself. That’s why they still feel fresh.

Do you bring specific Monk details—like clusters and stripped-down voicings—directly onto the guitar?

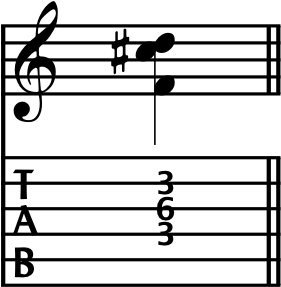

Some of them, yes. There’s a voicing I love that he used constantly: F, C-sharp, and D [plays the chord below]. You could think of it as a minor sixth stacked against a major sixth. That little cluster turns up everywhere—“Functional,” “Coming on the Hudson,” “Introspection.” It’s one of those signature fingerprints that identify a composer’s voice.

On guitar it’s a little awkward but very doable, and you can wring a lot of mileage out of it. So my “arrangements” aren’t fixed scores; they’re attempts to capture those Monk-isms directly, to translate the vocabulary. Sometimes the essence of a tune is voicing, sometimes it’s rhythm, sometimes it’s touch. I let the material dictate the approach.

How did you build your Monk book? Did you use transcriptions?

The main source was always the recordings. Monk himself didn’t want people reading his sheet music—he wanted you to learn by ear. That’s the most direct way to internalize his intent.

But I did use whatever resources made sense. There are transcriptions of some of the early Blue Note tunes—“Hornin’ In,” “Skippy,” “Humph”—and those are helpful because they’re so complex. Sometimes I’ll call a colleague and say, “What chord do you hear at bar 17 of this version?” Over time I built a notebook of these small decisions. It’s a composite method: records first, then references, then conversations, all stitched together into one mental songbook.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Eclectic Guitar to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.