Strange Incantations: Gwenifer Raymond Embraces the Wild Side of Fingerstyle Guitar

A conversation with the Welsh instrumentalist and composer, as well as a transcription from her most recent album

In the 1950s and ’60s, the guitarist and composer John Fahey spearheaded the development of an idiosyncratic approach to instrumental fingerstyle guitar, drawing equally from folk, blues, and contemporary classical sources, and played in nonstandard and often wild tunings. This niche genre came to be known as American primitive guitar and, for the most part, the musicians and their audiences have been overwhelmingly comprised of white men.

But American primitive guitar—oof, is it time to retire the term?—has become more inclusive in recent years as younger generations of players and fans gravitate towards its mélange of sounds. And one of Fahey’s most prominent acolytes is one of his unlikeliest, at least on paper: Gwenifer Raymond, the 38-year-old tech director of a video game audio company with a PhD in astrophysics, who lives and works in Brighton, U.K.

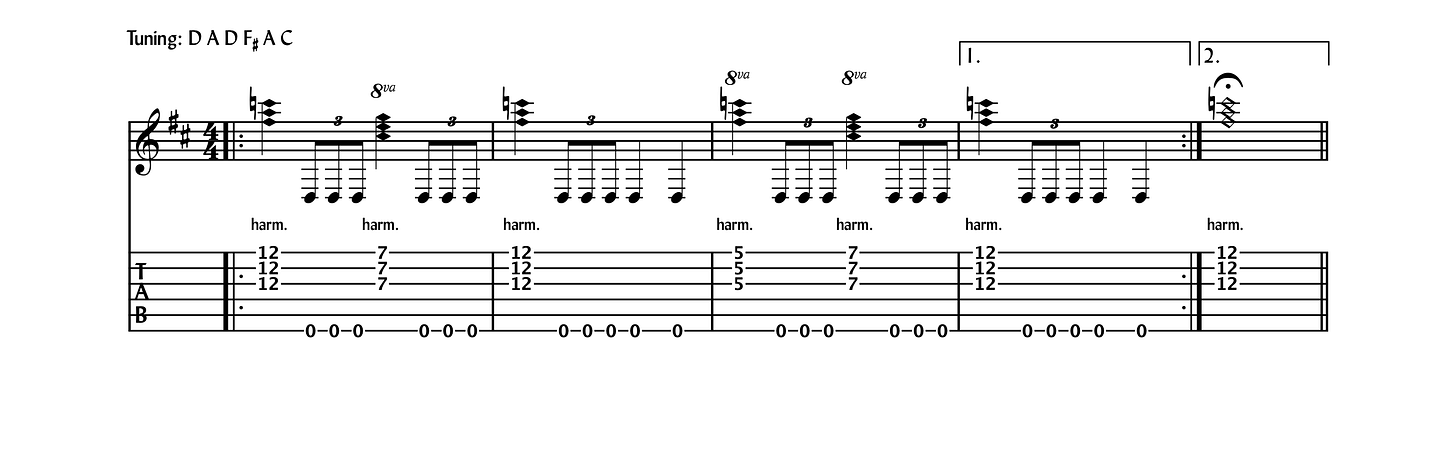

The specter of Fahey flickers through Raymond’s music, especially in a composition like “Requiem for John Fahey,” which I had the pleasure of transcribing for the January 2019 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine. But Raymond has put her own stamp on the idiom, with a sense of speed and velocity that comes from her time spent in rock bands, and a penchant for the weird and uncanny.

Having last exchanged emails with Raymond while editing her lesson on John Fahey’s arrangement of “Uncloudy Day” for AG, I recently checked in with the musician via Zoom from her home in Brighton. Among other things, she talked about the unexpected similarities she’s found between punk rock and old country blues, an upcoming sabbatical to work on her third studio album, and a fortunate and surprising gift from guitarist-composer Henry Kaiser. Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

You recently completed a North American tour. How has it been to play in the United States, where so many of your musical antecedents originated?

It’s my third official tour of the States. I’ve hit a lot of the same spots, in the Northeast and Midwest, and I do want to try to play farther west. It’s always great play in America, but it’s a strange place to play, because it is both very similar and very different to the U.K.—almost like almost like an uncanny valley situation. American audiences always seem appreciative and particularly enthusiastic, which is nice. Obviously, there’s a special kind of history in some of the places that I’ve been playing—Takoma Park [Maryland], where Fahey’s from, and Chicago or Detroit, where a lot of my other favorite musicians are from.

What was it like for you to discover the blues and John Fahey when you were growing up an ocean away in Wales? Did you have peers who are interested in the same music, or did you follow your own path?

I was a big punk and grunge fan, and a lot of my friends at the same age were into that scene. That’s why we were mates. At the same time, both of my parents listened to a lot of Dylan and Velvet Underground. I came to it through their common influences, which were a lot of early blues musicians. It seemed that anyone whose opinion was worth anything cited the blues as a reference. So I kind of found my own way to enter this sort of strange new land.

What about the blues struck you?

I liked a lot of more angular rock music, slightly weird and left of center, the stranger side of guitar-based rock. The sound that a lot of people think of when they hear the word blues is ’50s and ’60s Chicago blues. That’s not really my scene. I got into blues through guys like Mississippi John Hurt, who was a lovely, warm singer-songwriter and a fucking amazing guitar player, from a technical standpoint, as well as just having a lovely sound.

The first time I heard John Hurt, it didn’t even occur to me that was one guy. So when I discovered that it was, I wanted to pursue playing like that. And hearing musicians like Skip James, who was really strange; he didn’t sound anything like anyone else with his haunting sound… The whole angularity of it didn’t feel that different from some of the stuff I was otherwise listening to. From this kind of blues, I really got interested in hearing solo musicians, with very little between them and you, where you’re hearing the warts and all. There’s nothing to hide the performers, so it’s more of an intimate relationship.

When you discovered that the music was made not on multiple guitars but on one, how did you figure out how to do that yourself?

I just looked up a ton of tabs on the internet, and in guitar books like those by Stefan Grossman. Learning was a mechanical thing for me. It was about sitting there for hours, just playing the same riff over and over again, and trying to get it down. From a technical standpoint, a lot of how you play that music is like learning to play the drums—you have to grow that muscle memory and that independence to be able to play these different things at the same time.

After I’d been doing that on my own for a while, I found a really good fingerstyle teacher in Cardiff, not far from where I lived. I started going to him for a while, even though I’d been playing the guitar for ten years at that point. He was really great, and he played me my first Fahey record.

In a New York Times feature, you described John Fahey as “almost your mean uncle figure.” Can you expand on that?

Me quipping? Never [laughs]. Fahey is my favorite musician in the American primitive genre. You can sense his personality in his guitar playing. Even if he’s trying to hide something about himself, he can’t. He’s playing these lovely tunes, in major keys, but somehow it sounds kind of menacing. Having heard a lot of about him, he strikes me as an interesting character. If I had met him—he was an asshole, but I probably would have liked him and seen him less as a father figure than a strange uncle. Unfortunately, he was gone before I discovered him.

You played in grunge and punk bands as a kid, and occasionally as an adult. What did you take away from that music in how you approach the acoustic guitar today?

To a certain extent, I still like a good, solid riff—even if there are 25 of them in a song. I like the idea of formulating a song with strong riffs. It’s probably because of my background that I play pretty hard and quite fast. I’m not a fan of pretty, pastoral sounds or meditation music. I like the gothic and the the dramatic stuff, and I think that’s from coming up steeped in punk and grunge and hard rock and metal.

What is it about the dramatic and heavy sounds that speaks to you?

It’s the first music I liked—I had zero interest in music until I first heard Nirvana, when I was eight. It grabbed me and always has. It’s hard to explain; it’s just a natural gravitation I feel—not just in music but all media, especially horror movies.

It’s interesting that you have an astrophysics background and a professional life as a video game coder, but in your musical life, you work in a decidedly low-tech medium. How do these different areas interact with other?

They have certainly identified a certain attention deficit that I have, which might be present in my music. I got into science because I love the grand scale of the universe and all of those things. And the top two reasons I left science were that in order to pursue a career in science, you have to be beyond dedicated, and that I was playing too much guitar. Also, I have a horrible appreciation for printing the myth, which is not very good, as it doesn’t get you accepted into scientific journals. As for games, it was just that I’m good at maths—and I like video games. In a way, they inform each other by being almost polar opposites, which means that they don’t interfere. There’s a nice separation of the things, so you can approach each with an independence of thought.

What kind of video games does your work involve?

I’m currently the tech director of a game audio co-development studio, so I’m not personally working on anything right now. We do audio for lots of games, like Diablo and stuff like that. I’m actually about to go on sabbatical for two months to write a new album. I’ve never had that much time off work to pursue something, so that’s going to be a really interesting two months.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Eclectic Guitar to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.